Author: SJ

Walking along the beach at night or sailing on a darkened sea, you will often see sparkling lights in the water. This is bioluminescence—the emission of visible light by an organism as a result of a natural chemical reaction. A remarkable diversity of marine animals and microbes are able to produce their own light, and in most of the volume of the ocean, bioluminescence is the primary source of light. Luminescence is nearly absent in freshwater, with the exception of some insect larvae, a freshwater limpet, and unsubstantiated reports from deep in Lake Baikal. On land, fireflies are the most conspicuous examples, but other luminous taxa include other beetles, insects like flies and springtails, fungi, centipedes and millipedes, a snail, and earthworms. This discrepancy between marine and terrestrial luminescence is not fully understood, but several properties of the ocean are especially favorable for the evolution of luminescence: (a) comparatively stable environmental conditions prevail, with a long uninterrupted evolutionary history; (b) the ocean is optically clear in comparison with rivers and lakes; (c) large portions of the habitat receive no more than dim light, or exist in continuous darkness; and (d) interactions occur between a huge diversity of taxa, including predator, parasite, and prey.

via Haddock, Moline and Case (2010), Bioluminescence in the Sea – Annual Review of Marine Science, 2(1):443.

References and Further Information

- Haddock S.H.D., Moline M.A., and Case J.F (2010) Bioluminescence in the Sea, Annual Review of Marine Science, 2(1):443

- The Bioluminescence Web Page

- The Nature of Animal Light by E. Newton Harvey (available for download at Project Gutenberg).

They are an ancient species of flowering plants that grow submerged in all of the world’s oceans. Seagrasses link offshore coral reefs with coastal mangrove forests. Today, these “prairies of the sea,” along with mangroves, are on the decline globally. Scientists fear the diminishing vegetation could result in an ecosystem collapse from the bottom of the food chain all the way to the top.

Known as “hotspots of biodiversity,” seagrasses and mangroves attract and support a variety of marine life. However, worldwide damage and removal of these plants continue at a rapid pace. Changing Seas travels along Florida’s coastline to get a better understanding of the significant roles mangroves and seagrass play within the state. Can biologists prevent a negative ripple-effect throughout the marine food web before it’s too late? How will rising sea levels impact these plants as well at the communities that depend on them?

For further information on the Seagrass Watch program, please see the link and also “Ancient seagrass” for an article about seagrasses over 200, 000 years old.

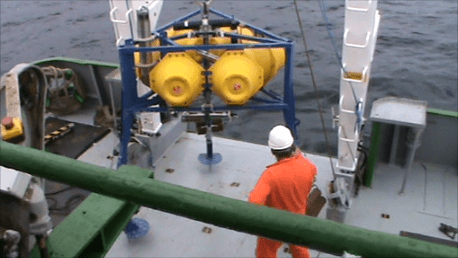

A benthic lander is a large three-legged frame with oceanographic instruments and sensors attached to it. These measure a range of parameters in-situ at the seabed; such as in this case, the current speed, temperature, salinity and turbulence. They are designed to operate in some cases 1000s of meters below the sea surface. Weights or ballasts are used to make the otherwise positively buoyant lander land down on the seafloor.

Here it was deployed from the Irish research vessel the Celtic Voyager in Galway Bay, West of Ireland, during a cruise by the National University of Ireland, Galway. The lander remains monitoring the conditions at the seabed for one month, in this case at depth of ~25m. Whilst out at sea during this period, it observes the impact of storm waves on the sediment transport. By making measurements at various heights above the seabed, it can obtain a profile of the benthic boundary layer and allow us to study how this changes during a storm.

By adding different sensors, you can also measure the chemical and biophysical properties of the water at the sediment-water interface. In-situ measurements allow us to study in the natural laboratory of the sea, without the need to remove anything. The measurements obtained by benthic landers are often used to verify as well as compliment laboratory results made under controlled situations.

It also has an acoustic positioning transponder which responds to the ship’s positioning call, to locate it for collection after its deployment. The weights or ballasts are released, with the buoyancy from the yellow floats allowing the lander to float back up to the surface.

This short video explains the Mapping the Deep project at Plymouth University. Mapping the Deep is also part of the UK’s Marine Environmental Mapping Programme (MAREMAP), which aims to achieve common, national objectives in seafloor and shallow geological mapping addressing themes such as habitat mapping, Quaternary science, coastal and shelf sediment dynamics and the assessment of human impacts and geohazards in the marine environment.

The IV International Rhodolith Workshop took place in Granada, Spain in September. Meeting every three years, delegates were from Brazil, Spain, United Kingdom, USA, Ireland, Mexico, New Zealand and Australia, as well as other countries. Rhodolith is a term largely used interchangeably to “maerl,” as free living non-geniculate coralline algae. Researchers came to share the latest research about one of the big four macrophyte dominated benthic communities (others being kelp beds, seagrass meadows and biogenic reefs) (Foster, 2001). Topics included taxonomy, ecology, management and conservation biology, genetics, geochemistry, evolution, palaeoecology, climate change studies and sediment dynamics.

Two excursion took place; the Granada coast to look at living rhodoliths and a two-day excursion to Almería-Cabo de Gata to observe both fossil and living rhodolith beds. The first excursion involved diving off the Granada coast or shorkelling to explore the small sea-caves along the coast. The second excursion involved exploring the processes responsible for deposition of rhodolith debris as cliff-deposits and how they have been preserved across geological time.

Further information can be found on the conference website. My poster presented to the conference can be found on the Griffith NUIG Biogeosciences website

References

Foster M, 2001, Rhodoliths: Between rocks and soft places, Journal of Phycology, Vol 37 Issue 5, 659-667